RISC-V and Post Quantum Cryptography

Building an ISA for modern cryptography (Introduction)

You may have heard about the Quantum Computers and impending doom they represent for public key cryptography: Q-Day. If you have not, let me refresh your memory.

The computers we used today are called “classical”, they rely on boolean logic (0 and 1, classical logic) and can be built out of classical logic circuits1 manipulating bits. A new type of computer, dubbed quantum computers, are built on top of quantum bits (or qubit). The logic is no longer classical, and the qubits represent a superposition of multiple states (and not just a single one, at least until they are read/projected).

Quantum Computers are very interesting beasts because they support a different type of algorithms whose complexity may differ widely from their classical counterparts. In particular, with a good enough quantum computers it seems to be possible to break some classical known hard problems (prime factorization, discrete logarithm) on which classical public key cryptography is built (e.g. RSA, ECDSA, ….). There is a lot of research and industrial efforts on-going to come up with such a workable quantum computer, reinforcing the feeling of a close threat (although maybe not imminent) to classical public key cryptography.

In this article, we will present Post Quantum Cryptography and how RISC-V is currently equipped to implement it and what the RISC-V community is looking at to improve the ISA efficiency for PQC. This blog post targets people with a superficial knowledge of cryptography (experts will be bored) and interest into RISC-V and how it behaves on those algorithms. Consider this article as an introduction. Hopefully, we will extend it with more detailed posts about each algorithms and RISC-V specification optimizations in the future.

When will Quantum Computing become a real risk ?

At the time of writing (end of 2025 / beginning of 2026), no Quantum computer with enough qubits is available to crack public key cryptography; it is believed that about a million qubits would be required for any non trivial application (Although you may see news about the quantum supremacy having been achieved from time to time. Quantum supremacy is the indisputable proof that a quantum computer performed a task way better than any classical computer could.

Note: the formal definition of quantum supremacy (sometimes called quantum advantage) does not mandate any usefulness for the task at hand. Here we are interested in when the task is actually relevant to breaking an actual cryptographic algorithm.

The day when a quantum computer will be able to break public key cryptography has been dubbed the Q-day and it will represent a turning point for cryptography: a lot of the asymmetric key cryptography in very wide use today (for symmetric key exchange, signature, …) would become immediately obsolete (unsafe).

For multiple reasons (including the possibility for an attacker to record current exchanges with the hope of being able to decrypt them after Q-day 2), the switch to quantum-resistant cryptography has accelerated lately and is now in full bloom. So if you think Quantum Computing will become an applicable reality at some point in the future, then it already constitutes a risk.

Transition to Post-Quantum Cryptography

The transition away from quantum vulnerable cryptography and to PQC is already on-going. Public agencies the word over have emitted recommendation and timelines for this transition. For example, the NIST3 (US) has published a timeline for the transition to quantum-resistant cryptography: NIST IR 8547 [NIST-PQC].

Standard bodies have published updated standards; e.g. PQC is available with TLS 1.3 (IETF standards for secure internet communications).

The industry is making the transition too. In May 2024 Google’s chrome switch to using TLS 1.3 and ML-KEM by default [GOO-PQC]. (We will see later that ML-KEM is a PQC type of key agreement. It literally means Modulo Lattice Based Key Encapsulation Mechanism).

In the last week of October 2025, Cloudflare (large provider of internet services) announced than more than half of the human initiated traffic was relying on PQC [CF-PQC-STATUS].

What differentiates Post-Quantum Cryptography ?

PQC is offering an holistic solution to the vulnerability of some classical algorithms for digital signature and key exchange to quantum computers. To do so, it is built on different sets of cryptographic primitives, believed to be much stronger against quantum computer attacks. Among those primitives, structured lattices and the Learning With Error (LWE) problem has been a key component of PQC cryptography and has been used for many of the current standards (ML-KEM, ML-DSA, …). Other quantum resistant primitives exist and NIST explicitly requested some efforts to come up with a Key Encapsulation Mechanism (KEM) scheme not based on structured lattices and is considering 4 algorithms not based on lattices. The NIST noted that no such DSA algorithm existed and requested additional non-lattice-based DSA algorithm [NIST-DSA]. This call lead to the standardization of digital signature SLH-DSA (as FIPS-205). SLH-DSA is using a hash-based scheme, independent from structured lattices.

As of end of 2025, 3 Post-Quantum Cryptography standards have already been ratified by NIST:

FIPS 203 (ML-KEM, Key Encapsulation, [FIPS203])

FIPS 204 (ML-DSA, Digital Signature, [FIPS204]),

FIPS205 (SLH-DSA, Digital Signature, [FIPS205])

FIPS 203, 204, and 205 were all published on August 13th 2024.

Note: in this post, we will not cover earlier stateful PQC signing algorithm: LMS (Leighton-Micali Signature) and XMSS (eXtended Merkle Signature Scheme). Those algorithms described in NIST Special publication [SP800-208] were excluded by NIST from their PQC competition because of their stateful characteristic.

We will first review those algorithms (superficially, more in depth references listed at the end of this post) before covering FALCON [FALCON], which although not yet standardized (as of early January 2026) should soon become FIPS 206.

ML-KEM is based on Crystals’ Kyber algorithm [KYBER] and ML-DSA is based on Crystals’ Dilithium algorithm [DILITHIUM].

SLH-DSA is a StateLess Hash-based Digital Signature Algorithm based on SPHINCS+ algorithm [SPHINCS+].

ML-DSA/FIPS-204 makes use of SHAKE128 and SHAKE256 from FIPS 202 [SHA3]. This algorithm, also known as SHA-3, is based on the Keccak permutation.

SHA-3, through SHAKE, can also be used in SLH-DSA [FIPS 205] which also specifies a SHA-2 based variant.

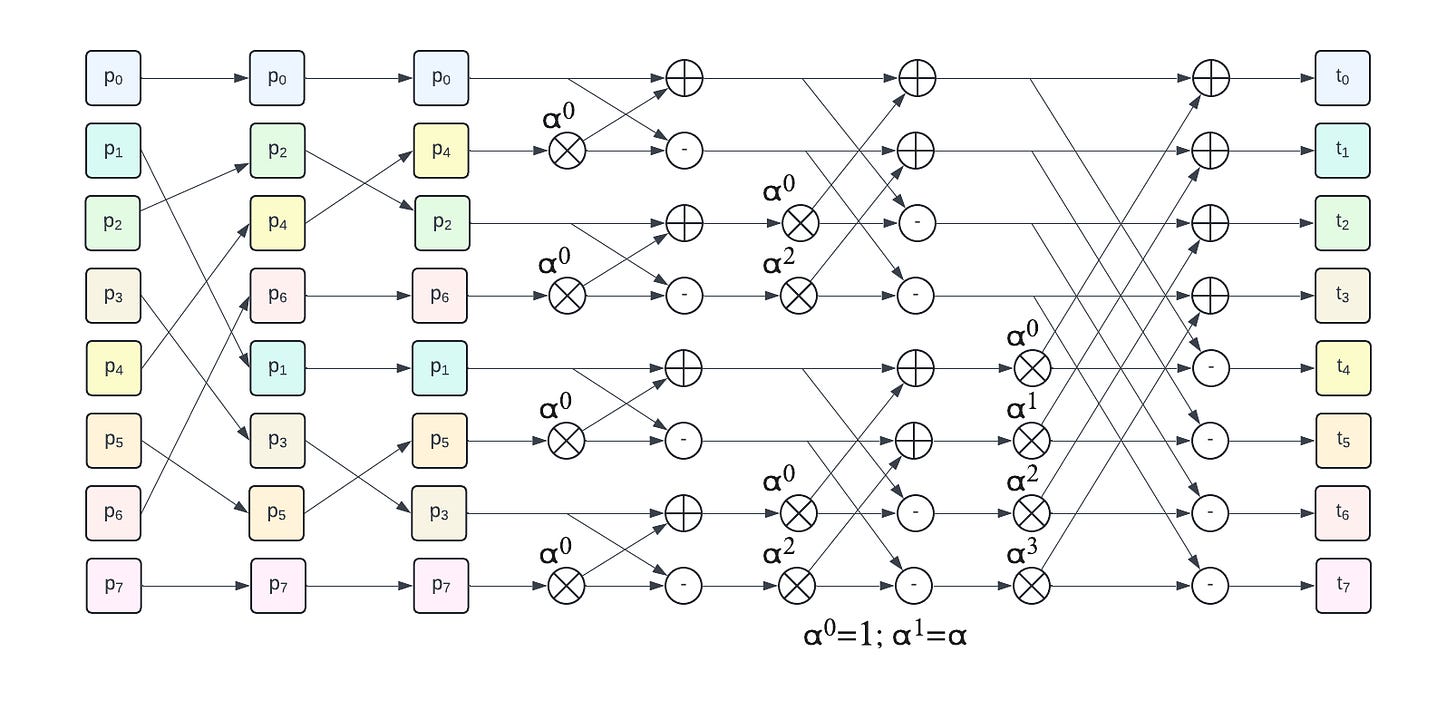

Both ML-KEM and ML-DSA make heavy use of modulo polynomial arithmetic: multiplying vector/matrix of polynomials with coefficient in a finite field. ML-KEM uses the modulo value 3329 while ML-DSA uses 8380417. They rely directly on the fast Number Theoretic Transform (NTT) algorithm. This and the use of SHA-3 constitutes the most computationally intensive parts of their respective algorithms (we share some numbers on how much Keccak represents in SLH-DSA and ML-DSA later in this post).

FIPS 203: ML-KEM / KYBER

FIPS-203 is a KEM, a Key Encapsulation Mechanism, designed to allow the sharing of a private key between two entities that wish to communicate securely. More precisely, the sender uses the receiver public key to encapsulate a key that the receiver is the only one able to decapsulate (thanks to its private/secret key). This mechanism differs from Diffie-Hellman where a common key is built by the sender and the receiver through a 2-way exchange.

ML-KEM has been designed to be resistant to Chosen Ciphertext Attack (in particular IND-CCA2).

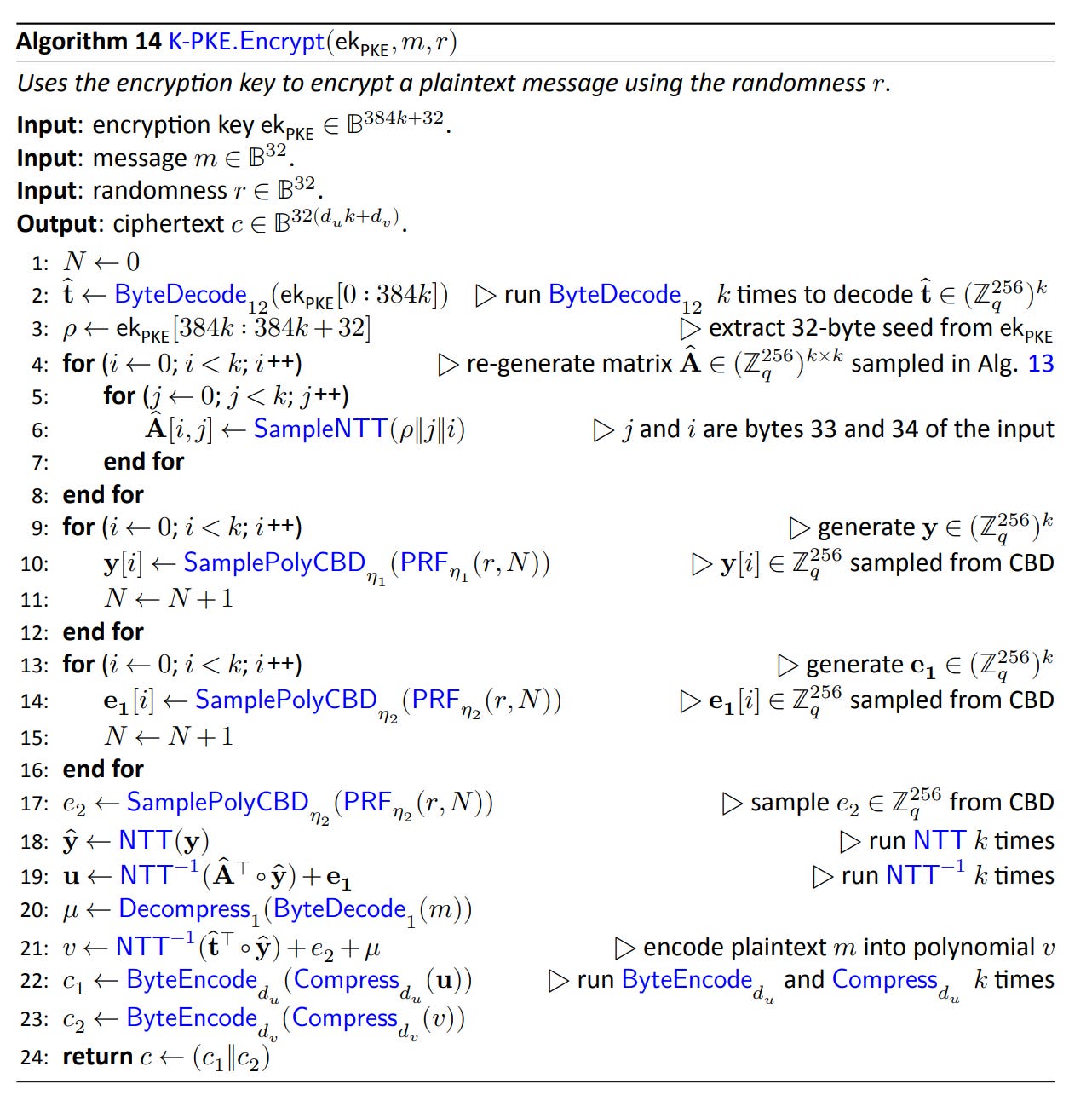

The screenshot below extracted from the [FIPS203] standard, illustrates the encryption algorithm of ML-KEM.

The secret key of Kyber is a vector of polynomials. The public key is a pair of a matrix and a vector of polynomials. Extra mechanisms (Compress/Decompress, key expansion) were introduced to limit the size of the public keys and the ciphertext.

Note: Kyber uses a variation of the Fujisaki-Okamoto transform to build a chosen-ciphertext-attack resistant Key Encapsulation Mechanism out of the chosen-plaintext-attack resistant public key encryption mechanism. This ensures that a modified ciphertext would lead to an invalid key with very high probability.

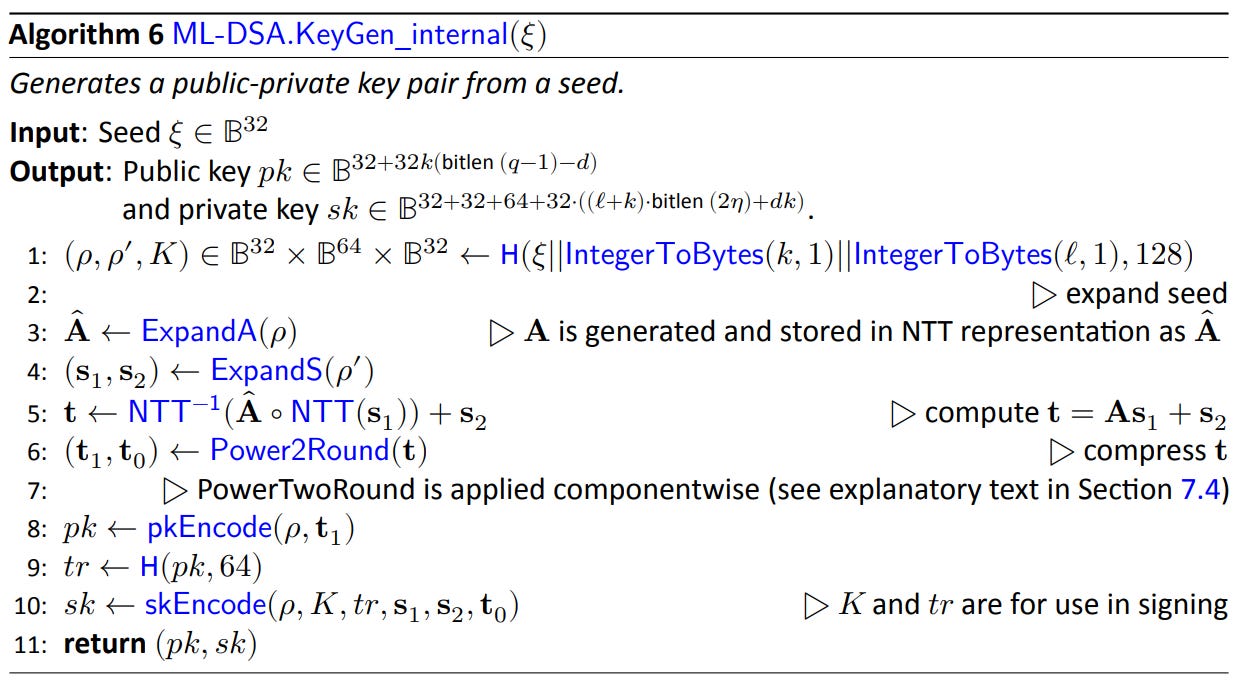

An important fact that we will discuss later is that KYBER (and also DILITHIUM / FIPS-204) uses the NTT transform heavily, in particular the public matrix A is actually sampled and used as Â, its NTT transform. Using the NTT transform significantly speed-up many KYBER and DILITHIUM operations.

Note: In both KYBER and DILITHIUM, directly sampling the NTT transform of a polynomial/vector/matrix can only be done when the polynomial coefficients are sampled uniformly at random. It cannot be leveraged for polynomials whose coefficients are constrained (example Kyber’s secret key s or DILITHIUM’s two secret polynomial vectors s1 and s2).

KYBER includes an “implicit rejection” mechanism: during key decapsulation, the decapsulated key is encrypted again and the result is compared to the ciphertext. If then do not match, the key is rejected and a pre-determined replacement is returned (this replacement is not expected to be used but it participates into the IND-CCA2 security assurance).

FIPS 204: ML-DSA / DILITHIUM

ML-DSA admits multiple parameter configurations. ML-DSA 87 private keys are 4’896 Bytes wide, its public keys are 2’592 Bytes wide, and its signature 4’627 Bytes.

The screenshot below, extracted from [FIPS204], illustrates the key generation part of ML-DSA.

DILITHIUM includes a rejection step during the signature phase. To ensure a signature can be verified appropriately and that the signature is not weak (with known vulnerabilities), some properties (constraints on the maximum magnitude of some polynomial coefficients) must be enforced. The signature algorithm loops until it generates a suitable signature. The number of iterations can vary, leading to different execution time (without this variance actually revealing anything about the secrets).

FIPS-205: SLH-DSA / SPHINCS+

SPHINCS+ is a digital signature algorithm (DSA) not based on lattices. The official name of the standard is Stateless Hash-Based Digital Signature Standard (SLH-DSA).

Contrary to FIPS-203 and FIPS-204, SPHINCS+ security is not based on the difficulty of the Learning With Error problem but on the preimage resistance of hash functions.

The algorithm relies on multi-level hash trees to sign messages: the root of the hypertree is used as the public key and the signature is made of a description (path) of how to obtain this public key from a set of tree leafs.

The public key size ranges from 32 to 64 Bytes, while the signature is much larger: from 7’856 to 49’856 Bytes.

SLH-DSA admits two hash functions: either SHA-2 or SHA-3 (FIPS-202) can be used.

FIPS-206: FN-DSA / FALCON

An other DSA based on Falcon [FALCON] has not been ratified just yet, but should be available shortly (as of the start of 2026). It is yet an other signing algorithm based on Lattices offering smaller keys and signatures than ML-DSA but requiring more computation time [FALCON-INTRO].

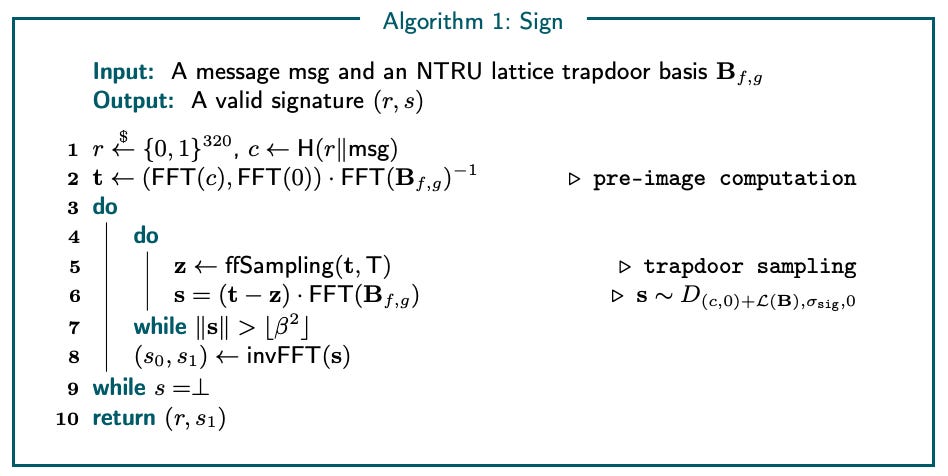

The screenshot below (extracted from [FALCON-ERR]) represents the signature algorithm of FN-DSA.

FALCON relies on floating-point arithmetic and there is research on-going to determine the impact of floating-point errors on FALCON [FALCON-ERR].

RISC-V Support for PQC

At the time of writing RISC-V does not offer any specific instructions designed for Post Quantum Cryptography (at least not in the official ratified specification). There is work on-going at RISC-V international (RVIA) to address this need, in particular in the Post Quantum Cryptography task group (mailing list, TG space). However PQC can already leverage existing extensions when being implemented on RISC-V. RISC-V vector (RVV) and vector crypto extensions in particular are very useful since they offer SIMD capabilities well suited to accelerate PQC which exhibits a wide level of data parallelism.

PQC Software ported to RISC-V

In this section, we will look at four existing PQC software libraries: mlkem-native, mldsa-native, slhdsa-c, c-fn-dsa and how they behave on RISC-V. Note that RISC-V has already been added as a native target for mlkem-native (a RISC-V specific optimization effort has already been made) while mldsa-native (contrary to what its name may indicate), slhdsa-c, c-fn-dsa have not received such focus just yet (our benchmarking evaluates the generic implementations).

The goal is not (yet) to optimize PQC on RISC-V but simply to illustrate the current level of performance (and that generic PQC implementations can already be deployed on RISC-V platforms).

Benchmarking was performed on the BananaPi F3 with SpacemiT X60 CPU cores (including RVA22 profile with the RVV 1.0 option). I made no change to the software primitives. I simply instrumented or modified the instrumentation of the performance benchmarks to be able to retrieve cycle measurement on Linux running over a RISC-V platform.

The compiler used in clang version 18.1.3.

The report metric is algorithm latency, in machine cycles.

The first set of results is for ML-KEM. The 3 security level are represented: ML-KEM 512 offers a security level equivalent to 128 bits, ML-KEM 768 offers 192 bits and ML-KEM 1024 offers 256 bits (equivalent to AES 256). As expected the latency of each operation grows with the security level. It can also be noted that the decapsulation is always the slower operation followed by the encapsulation and eventually by the key pair generation.

ML-KEM is the only algorithm that has received specific attention on RISC-V (at least when it comes to the implementations we tried). For the others, we benchmarked generic implementations.

The second benchmark covers ML-DSA <NM>. The number <NM> indicates the two dimensions of the public key matrix A: NxM polynomials. The security level grows with the size of the matrix (as well as the latency). Signing is the slowest operations, followed by signature verification and key generation (the latter two exhibit similar level of performance).

Since ML-KEM and ML-DSA do not support the same use cases, making comparison is pointless but we will be able to compare the various DSA algorithms.

The next algorithm is SLH-DSA. The set of parameters include both SHA-2 and SHAKE (Keccak/SHA-3) based configurations, it also includes both “s” small (signature size) and “f” fast variants.

As for ML-DSA, signing is by far the slowest operation. But contrary to ML-DSA, key generation and verifying exhibit a wider variety of speed. The small “s” variants have much faster verification compared to key generation, while the fast “f” variants exhibits similar performance for KeyGen and Verify, with generally (but not always) a slight benefit for key generation.

The SHAKE variant is always slower than the SHA2 one. Note that the hardware platform we are using (the BananaPi-F3) does not implement any RISC-V Vector Crypto extensions. It is highly likely that those extensions (in particular Zvknha and Zvkb) would accelerate the hash part of SLH-DSA.

Note: the visualization below (slhdsa-c) uses a different scale for each subgraph: the differences in latency were too large for us to use a uniform scale without making some of the smaller values disappear.

At the moment SLH-DSA is widely slower than ML-DSA. This would need to be investigated in details, but it is highly likely that implementing hash functions with the generic RISC-V Vector extensions does not provide the best results on RISC-V. It would be interesting to benchmark an implementation with support for the vector crypto extensions.

The last set of benchmarks covers FN-DSA (based on FALCON). The algorithm is not available in https://github.com/pq-code-package so we used Thomas Pornin’s (FALCON’s author) implementation: https://github.com/pornin/c-fn-dsa/. The code has only been modified to use the Linux PERF API for cycle count (no specific optimizations for RISC-V were made).

The FN-DSA benchmarking results are very telling: FALCON verify operation is one order of magnitude faster than signing, which is more than one order of magnitude faster than key generation. Out of the box, FALCON is the fastest PQC DSA algorithm on RISC-V when it comes to signature verification. Signature speed is comparable somewhat to ML-DSA, but key generation is much much slower.

This aligns with FN-DSA / FALCON intent: providing a PQC scheme with fast signature verification that could be implemented on smaller / less powerful platforms (e.g. embedded).

How can RISC-V Support for PQC be improved ?

Let’s review in details 3 domains which can benefit from ISA support: modular arithmetic, NTT and Keccak acceleration and list (non-exhaustive) some existing efforts to speed-up them up on RISC-V.

Do you really need modulo arithmetic ?

The actual question is do you need hardware/instruction acceleration for the direct computation of multiplication/addition in the finite fields used in ML-KEM and ML-DSA. I believe the answer to be a resounding: No (I might be proven wrong).

It is easy to transform the modulo operation into a small sequence of simpler operations, often around a multiplication by an approximation of the inverse of the modulo (sometimes multiplied by 2^32). Those techniques (Montgomery, Barrett, Plantard) remove the need for a fast modulo/remainder operation.

When done carefully (for example by ensuring that the result falls into the upper 32-bit of the result), some pre-existing instructions can be used. For more detail, you can check our implementation of Barrett’s reduction for the polynomial multiplication using RVV’s vmulh.vv in:

This does not require any ISA extension, and can leverage existing vector datapath implementations. Here, RISC-V RVV 1.0 seems sufficient for a performant implementation of modular arithmetic.

Accelerating NTT

Accelerating NTT is a general topic of interest: it is critical for PQC, but also for FHE (Fully Homomorphic Encryption) since some algorithms share the same primitives (module learning with error).

There is a general community effort around accelerating NTT on RISC-V. For example, fhe.org organized a technical talk by Alexandre Rodrigues on the subject: Accelerating NTT with RISC-V Vector Extension for FHE.

In the PQC world, both ML-KEM and ML-DSA make heavy use of NTT also in different settings. Dillon D’s worked on NTT optimization over RISC-V for ML-KEM ‘s precursor, Kyber: RISC-V Optimized NTT in Crystals Kyber [RV-NTT].

One of the performance bottleneck of NTT/FTT on CPU is its access patterns, the fast transform require non contiguous accesses or re-ordering the data to ensure in-place transform can be achieved.

We covered this in this post:

RISC-V (Vector) offers multiple way to implement those access patterns, but the performance depends on the quality of the underlying implementation.

Accelerating SHA-3/Keccak

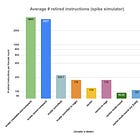

SHA-3 and in particular the sponge function Keccak f1600 is a critical component in the performance of numerous PQC algorithms. For SLH-DSA SHAKE-Based, it oscillates around 90% when executed on our benchmarking RISC-V platform as illustrated by the plot below:

Keccak is also used in other algorithms such as ML-DSA where it is used to generate key assets from seed (reducing the storage size required for the public key for example).

As can be seen on the plot below, Keccak represents a large portion of any ML-DSA operations, ranging from 15% up to 60%.

Note: The wide range represented by Keccak in the signing step would required some investigation.

Overall Keccak represents a substantial part of ML-DSA execution time on RISC-V. Thus optimizing Keccak on RISC-V is critical for PQC performance.

Two years ago we explored Keccak performance on RISC-V, covering RISC-V Vector:

We focused on a single stream implementation of Keccak but PQC, and mldsa-native in particular, can make use of parallel implementations computing multiple independent Keccak f1600 permutations in parallel (which should be well suited for implementation with RVV, in particular with large VLEN).

In our experiment, the Keccak f1600 permute used in ML-DSA takes about 3’550 cycles (executing the full 24 rounds). RISC-V Post Quantum Cryptography task group (PQC TG) is working towards a proposal to considerably speed-up Keccak implementation by encapsulating a full Keccak round (or even multiple rounds) into a single vector instruction. Keccak does not require much hardware which could make a full round suitable for a full hardware implementation.

Conclusion

Post Quantum Cryptography is rapidly picking up steam and is highly likely to become ubiquitous soon even without the apparition of workable quantum computers. Almost 10 years after NIST kicked-off their PQC standardization process (Dec 2016) a lot has happened: 3 PQC algorithms (1 key encapsulation, ML-KEM/Kyber and 2 digital signatures, ML-DSA/Dilithium and SLH-DSA) have been standardized and 1 future digital signature algorithm is in the works (FN-DSA/Falcon). Modern processors must be able to support PQC efficiently and RISC-V community is working towards enabling the ISA for that purpose.

We measure the current performance of some PQC implementations on a RISC-V platforms and we listed some direction for improvements.

We have only consider the performance side of the RISC-V implementation without covering the security side. All the implementations we evaluated are constant time but they do not offer extra security insurance against other side channel attacks. The RISC-V and Cryptography communities are considering those challenges and it is likely than a dedicated answer will be offered in the future for implementors looking to offer high assurance cryptography implementations.

If you are interested in contributing to the RISC-V PQC (or security) effort, please connect with RVIA Post Quantum Cryptography task group (PQC TG) through the mailing list. or with RVIA numerous security and cryptography task groups and special interest groups (HAC TG, Crypto SIG, Security HC, …).

Over the coming months, I will try to experiment with optimizing some of the implementations listed in this blog post and I will report my progress / failures / successes in this newsletter. stay tuned ! [and subscribe if interested :-)]

Reference(s)

Specification(s):

[FIPS203] FIPS-203: Module-Lattice-Based Key-Encapsulation Mechanism Standard (pdf)

[FIPS204] FIPS-204: Module-Lattice-Based Digital Signature Standard (pdf)

[FIPS205] FIPS-205: Stateless Hash-Based Digital Signature Standard (pdf)

[SHA3] FIPS-202: SHA-3 Standard (pdf)

[DILITHIUM] https://pq-crystals.org/dilithium/index.shtml

[SPHINCS+] SPHINCS+ algorithm

[SP800-208] Recommendation For Stateful Hash-Based Signature Schemes

[FALCON] Falcon: Fast-Fourier Lattice-based Compact Signatures over NTRU (and its official website)

Other Reference(s)

[NIST-RFC] NIST request for submission to the PQC standardization process (pdf)

[NIST-PQC] Initial Draft of NIST Internal Report 8547 (pdf), “Transition to Post-Quantum Cryptography Standards”

[GOO-PQC] Google’s blog: Post-Quantum Cryptography: Standards and Progress

[CF-PQC-SIZING] Cloudflare’s blog: Sizing Up Post-Quantum Signatures (Nov’21)

[CF-PQC-NIST] Cloudflare’s blog: NIST’s pleasant post-quantum surprise (Jul’22)

[CF-PQC-STATUS] Cloudflare’s blog: State of the Post-Quantum Internet in 2025 (Oct’25)

[NIST-DSA] Post-Quantum Cryptography: Additional Digital Signature Schemes

[FALCON-ERR] Do Not Disturb a Sleeping Falcon (pdf), X. Lin et al

[RWE] A Riddle Wrapped in an Enigma (pdf), Koblitz and Menezes take on NSA 2015 Policy Statement for transition to PQC

Professor Alfred Menezes’ Cryptography101.ca (a goldmine for material on cryptography, in particular PQC, I also recommend his youtube channel)

[FALCON-INTRO] Prof B. Buchanan’s Get Ready for FN-DSA: Slower Than Dilithium But Smaller Keys/Ciphertext

[RV-NTT] Dillon D’s RISC-V Optimized NTT in Crystals Kyber (slides)

[RV-PQC] RISC-V-based Acceleration Strategies for Post-Quantum Cryptography

Software:

pq-code-package/mlkem-native implementation of ML-KEM (github)

pq-code-package/mldsa-native implementation of ML-DSA (github)

pq-code-package/slhdsa-c implementation of SLH-DSA (github)

sphincs/sphincsplus implementation of SPHINCS+ (github)

Thomas Pornin's (Falcon's author) implementation of FALCON (github)

XMSS reference implementation (github)

https://github.com/mupq/pqriscv (github)

Although transistors work thanks to quantum effects, and quantum mechanic also explains some side effects that mess with one my expect a perfect transistor to do, the logic they implement is not quantic in nature.

Sometimes called Harvest Now Decrypt Later / Store Now Decrypt Later attacks

NIST: US Institute in charge of cryptographic specifications and policies, amongst other things.

Fprox, I was not actually trying to directly compare "classical" encryption algorithms with PQC. We are both aware of Keccak hardware optimization being proposed for accelerating PQC in RISC-V, and I was hoping to get a rough idea of how much faster this would be. I know you can't directly measure it until there's hardware (or, at least, cycle accurate simulation/emulation), but there are similarities in how the calculations are done.

I agree, AES may not be the proper baseline to compare against, but RISC-V vector crypto does not directly accelerate the other algorithms, although they could use the Zvknh, Zvkg, Zvbc, and bit manipulation extensions for building blocks.

One other thing I forgot to comment on earlier: a major stumbling block for FALCON is its use of floating-point arithmetic. This is unique among cryptographic algorithms, and the idiosyncrasies of the IEEE754 standard cause those who analyze this algorithm a lot of headaches. I think the problems are two-fold: 1) dealing with infinity, NaN, and subnormals and 2) no guarantees of Data Independent Execution Latency (DIEL), making it harder to create constant-time implementations.

Correct me if I'm wrong, but I believe FALCON data does not source or produce infinity, NaN, or subnormals. It is also using Double-Precision (64-bit) floating point even in hardware that does not support it (e.g., some old 32-bit ARMs). There is some sample code out there that implements the floating-point instructions in software, but these are horribly slow (on the order of 10-20x the number of cycles that a hardware instruction would take).

Even with software implementation, FALCON is considered to be "fast enough", compared to other PQC. Not having to implement floating-point hardware + registers may be the right tradeoff in small processors.

My understanding is that only a small subset of floating-point instructions are needed by FALCON (fadd/fsub, fmul, maybe some of the conversions, but not fused mul-add, and not fdiv/fsqrt). The ones that are needed *can* be implemented with DIEL conformance, but this would have to be codified into the ISA before implementers would trust that.

Fprox, informative as usual. I know it isn't apples-to-apples, but I'm curious how AES latencies compare.