IEEE-754: THE floating-point standard

A specification to rule them all

Recently, the IEEE-754 standard (initially published in 1985) celebrated its 40th birthday. A very nice ceremony was put together by Leonard T. and the local chapter of IEEE at University of California in Berkeley (UCB).

This is as good reason as any to talk a bit about the standard and share some references through this brief history (don’t expect too much technical insights or any nuggets in this article, I was not born in 1985 and did not contribute anything to the standard, but I am happy to stand on the shoulder of giants).

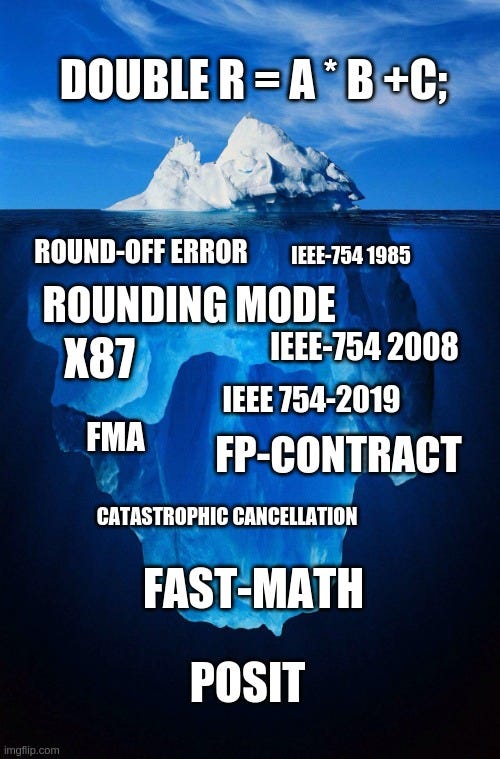

The IEEE-754 is the standard that specifies the binary floating-point arithmetic, it is ubiquitous and is used across most computing platforms to represent real numbers and perform mathematical computations. When you manipulate a float or double (e.g. in C), you are manipulating numbers encoded according to the IEEE-754 standard, and when you perform operations on those numbers, the arithmetic is also specified by the IEEE-754 standard.

IEEE-754 has emerged as a key standard for computers. They exist numerous other number representations but as of 2025 the binary floating-point representation specified in the IEEE-754 is the most used and widespread.

Before the standard: the Wild West

Floating-point number representations admit a lot of possibilities: it entails defining formats, precision, rounding, behaviors on overflow and underflow, the definition of special values. This creates a very large space of possible specifications with different trade-offs. Before the standard, there was definitely of plurality of incompatible implementations, where each manufacturer felt free to make different choices (and sometimes even different choices between two product lines of the same manufacturer). Porting of numerical programs was difficult, result were less predictable (they are not totally predictable today, in particular depending on what options are used to build a program, and what library are used, but the determinism was greatly improved by the IEEE-754).

The original standard (1985)

The Original standard was ratified in 1985, but the effort was started much earlier.

Numerous key contributors participated in the establishment of the standard amongst them Professor Kahan (UCB) might be the most famous. If you want a good transcription of how the standard came to be and the discussions and rationale behind it, I strongly recommend this abbreviated version of an Interview of professor Kahan: An Interview with the Old Man of Floating-Point (I found the section on why and how the gradual underflow came to be integrated in the standard particularly interesting). David G. Hough IEEE article, The IEEE-754 Standard: One for the History Books [7], is also a very good read on the topic (and on the IEEE-754 in general).

The standard is recognized for properly specifying formats, numerical behaviors, special cases and providing a canvas for handling floating-point exceptions occurring in numerical programs. It rapidly became the standard for floating-point in CPUs and other type of processing units.

The 2008 revision: the age of the FMA

IEEE mandates that a standard must be revised every 10 years to stay valid (else it gets deprecated). Priori to 2008, the standard was quietly renewed a few times [7]. 2008 was the occasion for what one might called a major revision. David G. Hough article [7] contains a very nice description of the 2008 effort and the contentious points (in particular discussion around decimal floating-point encoding).

The 2008 revision of the standard introduced a few corrections and a few novelties: integrating decimal floating-point, the half-precision format (binary16), the FMA, and specification for elementary functions.

Among the novelties, the Fused Multiply-Add (FMA) operator is a very nice addition. This operator, implementing a * b + c with a single rounding, appeared in the early 90s in hardware implementation (most notably IBM’s processors) and rapidly became a key component of the numerician toolbox. The single rounding allows for higher throughput and lower latency implementation than a split multiply-add (although the extended product introduces some challenges), but its key benefit is numerical: the single final rounding makes it quite useful to evaluate accurately intermediary errors (e.g. when implementing Newton-Raphson iterations or when implement a double-word split product). This operator is available in all the most widespread ISA: x86, Power-PC, ARM, RISC-V and many others.

The 2008 revision also integrated decimal floating-point (which was not in the original 1985 standard but had been specified in a separate standard for radix independent arithmetic: IEEE-854, ratified in 1987).

The specification of elementary functions mark the start of an effort to specify what a mathematical library should look like. Such effort continues with the CORE-MATH project [8] and may become more prevalent in the 2029 revision.

The 2019 revision

The 2019 revision was lightweight compared to the 2008 one.

from Wikipedia’s page :

It incorporates mainly clarifications (e.g. totalOrder) and defect fixes (e.g. minNum), but also includes some new recommended operations (e.g. augmentedAddition).

Once again David G. Hough’s article [7] offers a good overview of what was covered in the 2019 revision.

The Augmented operations are an interesting addition, as they offer a way to implement exact arithmetic: using two (non overlapping) words to represent the result, one for the original rounded result and one for the error. This could lead the way to more widespread implementation of 2-sum for example.

Another improvements brought by the 2019 revision was deprecating non-associative minimum and maximum operations (in the presence of NaN) and introducing new, cleaner, operations.

The rationale and changes behind the 2019 revision of the IEEE-754 standard can be found in [9].

The future: 2029 revision and P3109

As of 2025, work on a new revision of the IEEE-754 standard has started (since 2024-ish) with a sanctioned IEEE working group working on a revision of the standard. The revision is planned for 2029 [10].

At the moment, the revision is considering multiple subjects: from clearing some definitions to mandating correctly-rounded functions in any compliant implementation.

There is a parallel effort, the IEEE P3109 working group [5], addressing the need for a specification for smaller formats (16-bit or less). It aims at addressing the specific constraints of arithmetic for machine learning. We covered P3109 some time ago in our review of 8-bit formats:

Partial Taxonomy of 8-bit Floating-Point Formats

This blog post is not centered on RISC-V, it reviews recent developments in Floating-Point arithmetic around the standardization of small (8-bit) floating-point formats.

Conclusion

IEEE-754 is not the only type of floating-point arithmetic that exists, and several other formats co-exists: Unum/Posits, Logarithmic Number System (LNS), fixed-point, … However non of the other formats has had the same success so far, but hopefully people will keep proposing formats and improvements.

One of the area where something new is happening is on the small size end of the format spectrum. The need for smaller formats has seen a new explosion of vendor specified formats (e.g. NVIDIA’s NVFP4, Microsoft’s msfp8, …). Some standardization efforts, e.g. OpenCompute’s OFP8 or MX-Formats, have also emerged and are already being implemented. It is not clear how they will co-exist with the P3109 effort. OCP’s specifications seem to have a lot of momentum at the moment and P3109’s ratification will still take some time. We can hope that this will not end up in a fragmentation of the format landscape (similar to the pre-1985 era) as this would make life more difficult for software developers and users.

Reference(s):

[0] What Every Computer Scientist Should Know About Floating-Point Arithmetic, David Goldberg (pdf)

[1] Professor Kahan’s Wikipedia page (html)

An Interview with the Old Man of Floating-Point (Summary of an interview of Pr. Kahan in 1998)

[2] IEEE 754-1985 original Standard original standard (IEEE webpage)

[3] IEEE 754-2008 Standard first revision (IEEE webpage)

[4] IEEE 754-2019 Standard second revision (IEEE webpage)

[5] IEEE P3109 Working Group (IEEE webpage) and [5.1] github repo

[6] Floating-Point on NVIDIA’s FPU (pdf)

[7] The IEEE-754 Standard: One for the History Books (pdf) by David G. Hough (chair of the 2019 revision)

[8] The CORE-MATH project, Inria’s project to demonstrate feasibility of a correctly rounded mathematical library of elementary functions.

[10] P754 Standard for Floating-Point Arithmetic (On-going IEEE project for 754 revision)